The legal-ethics rules don’t specifically govern the position of a lawyer’s zipper, though when applicable Model Rule 1.8(j) will generally mean it must remain in the “up” position in the vicinity of a client. Florida has adopted a version of that rule, which lawyers in that state should consult in similar situations well before such a situation arises. See Florida Rule Prof. Conduct 4–8.4(i). Violating it is likely to get you disbarred. While this case did not involve that particular rule, it involved somewhat similar conduct. Result: disbarment.

This now-former Florida lawyer, who would prefer to remain anonymous but whose name is Andrew Spark, previously appeared in Assorted Stupidity #109, reaffirming the principle that appearing in said category may not bode well for one’s future practice of law. (Not because of that appearance, so far as I know, but because the underlying conduct is, by definition, stupid.) Here’s that paragraph:

On December 17, [2017,] a 54-year-old Florida attorney was booked on charges arising from his alleged plan to record himself having sex with an inmate, something detectives alleged he has done at a variety of Florida jails. The man was actually setting up “scenes,” not just recording the acts, detectives said, though the report does not say he was posting or selling actual movies in which he could personally be identified. That reduces the stupidity factor only slightly, however, because he did film the “jail surroundings” and each inmate’s I.D. card, as well as depositing payment in their prison commissary accounts. Detectives received a tip about the attorney’s conduct, and made a short film of their own.

According to the referee’s report on this matter, the detectives’ film ended with a scene in which they entered the visitation room “and arrested respondent who had his zipper down,” which was bad for him but gave me a handy euphemism to use in a headline.

Their film, his films, and other evidence led to criminal charges, and Spark later pleaded guilty to misdemeanor solicitation and “introduction into or possession of contraband in a county detention facility,” which is a felony. (I think the “contraband” was the tablet he used for the recording, though the report isn’t clear.) In fact, he pleaded guilty to two sets of those charges, because he did this at least twice.

This is bad, of course, not just because these are crimes but because he was preying on women who were vulnerable for several reasons, not least because they were inmates being approached by a lawyer, and in a room that was not monitored because it was meant for privileged conversations. He argued that it was all fine because they consented, but someone in that situation isn’t likely to feel free to say no. A similar problem is why most jurisdictions have adopted some form of Rule 1.8(j): clients are often in vulnerable situations, and lawyers should not be taking advantage of that. These women were not Spark’s clients, but they were vulnerable.

Also, Spark had to lie in order to get into these situations, such as by claiming that he was at the facility to meet with a client. And because he had committed a felony, all this was more than enough to get him charged with violating Rule 8.4(b), the one about not committing “a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects.”

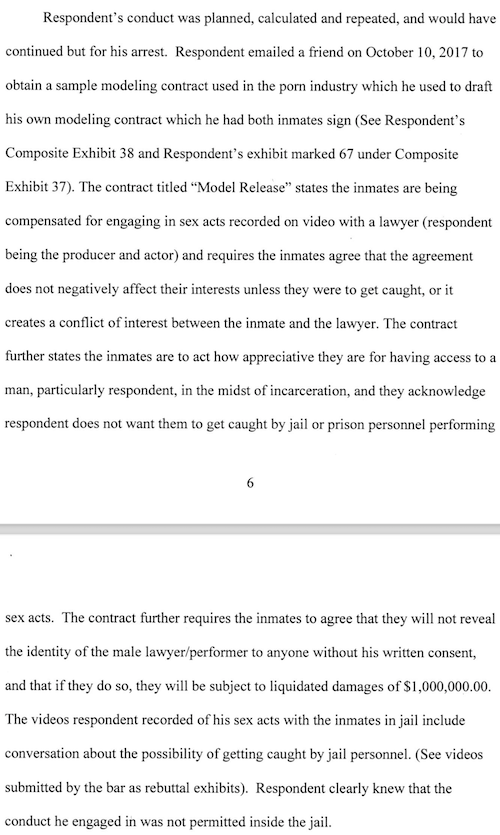

Speaking of fitness as a lawyer, the contract that Spark drafted up for these women also suggests he wasn’t a very good one. Yes, he had them sign contracts, which he drafted based on an example he got from a friend in the adult film industry. Based on the report’s description, these “modeling contracts” would have been unenforceable under the circumstances, so all they ended up doing was prove Spark knew what he was doing was wrong:

Looks like he didn’t know much about contracts, though.

While Spark did not contest the referee’s findings (or the court’s disbarment order last week), he did try to defend himself to some extent during the initial proceeding. Let’s just say the referee found the evidence supporting his “sex addiction” defense came up a little short, and also that if you do what Spark did here, evidence “showcasing [your] membership on bar committees … and thank you cards and letters” received during your career is not likely to help much.

It’s nice to get a thank-you card, of course. You should frame it! Just don’t expect it to have much weight in a disbarment proceeding.