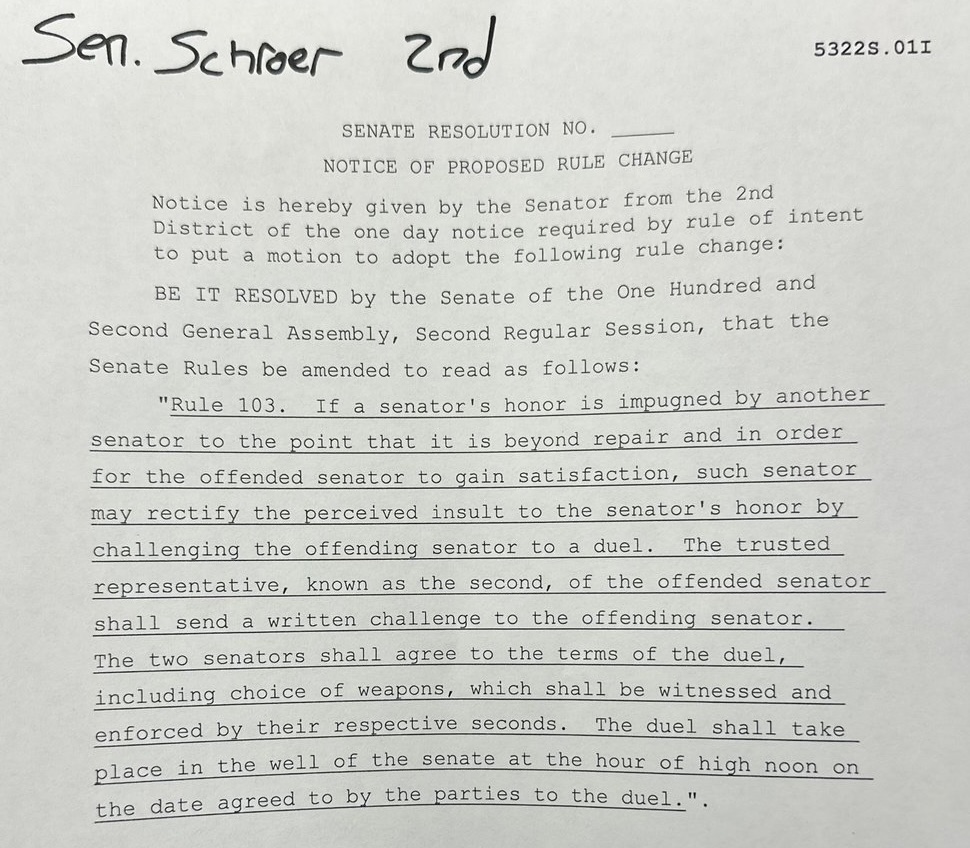

Some people are considering it, at least. This is based on a recent proposal to amend the Missouri Senate’s rules to allow dueling if “a senator’s honor is impugned by another senator to the point that it is beyond repair,” with said duel to take place “in the well of the Senate at the hour of high noon on the date agreed to by the parties to the duel”:

But they aren’t considering it that seriously, at least not yet. The image above was posted to Twitter by whoever runs the @MoSenDems account. The post stated that the sponsor had “filed a proposed rule change to allow Senators to challenge an ‘offending senator to a duel.'” It may have been “filed,” if that’s how the number in the top right gets assigned. But it never got a resolution number, and you won’t find it on the Missouri Senate’s moderately usable website. So it was more of a proposal for a proposal. Probably.

“Senator [Nick] Schroer is deeply committed to restoring a sense of honor in the Missouri Senate,” Schoer’s chief of staff told Newsweek, sounding a little like maybe they were serious about this? But, he continued, “[w]hile the idea of a duel may have been suggested in a metaphorical sense,” which sounds like they weren’t serious, but also uses “may” and the passive voice, “the core message is about fostering respect and reminding members that the words used in a debate may have real consequences.” See, there I thought you were speaking metaphorically about violence and then you said “real consequences,” which almost seems inconsistent with that. So it’s a bit of a puzzle.

In any event, the proposal wasn’t formally proposed, so for now it’s just talking.

Of course, dueling was at one point fairly common in the United States, at least among those who aspired to political office and yet still purported to have honor capable of impugnment. It was common enough, in fact, that many laws and rules were enacted to try to deter it. See, e.g. “Dueling Still Not Advisable in Oregon” (May 12, 2017) (discussing state constitutional provision barring duelers from holding political office); “No-Dueling Promise May Be Dropped From Kentucky Oath” (Mar. 10, 2010) (discussing similar provision in the oath new Kentucky lawyers are still required to take).

Missouri has no such provision, so far as I can tell, except for a statute that applies only to the military. Mo. Rev. Stat. § 40.385. This is despite the apparent frequency of this nonsense in that state before the Civil War. In fact, an essay on the Missouri Secretary of State’s website—”Crack of the Pistol: Dueling in 19th Century Missouri“—describes dueling as “a standard political weapon” during that time.

Around 1800, what had been a “small sandbar” in the Mississippi betwixt Missouri and Illinois “grew to island proportions.” (See also this essay, from the Illinois point of view.) After trees grew on it, affording some seclusion, and because it was considered a sort of neutral zone not in either jurisdiction, it became “an ideal site for duels, cock fights, and illegal boxing bouts.” That’s how it became known as “Bloody Island.”

Whether it was in fact a neutral zone in which the murder of people and poorly trained chickens was legal, or at least not illegal, is extremely doubtful. State boundaries were not exactly defined with scientific precision, but the relevant laws defined this border as “the middle of the Mississippi River.” That would have put this area in Illinois (where it is today, though not an island), and I’m fairly confident shooting people was illegal in that state at the time. (A similar “neutral zone” claim is sometimes made about an area of Yellowstone Park, but don’t believe that one, either.)

Regardless, not only did men go there to shoot at each other, many of these idiots were or became lawyers and politicians. As the Missouri essay explains, Thomas Hart Benton shot a guy in the throat on Bloody Island in 1817, and after he lived, Benton challenged and shot him again a few months later. The successful murderer then represented Missouri in the U.S. Senate for 30 years. In 1831, a member of Congress and another man both died in a duel, having agreed to shoot at each other while only five feet apart. And in 1856, in the “last known duel in Missouri resulting in bloodshed,” one man escaped injury and the other, shot in the leg, “limped for the rest of his life.” The limper became a U.S. senator and later the governor of Missouri; his opponent became the second Confederate governor of Missouri (well, part of it).

As that should remind us, the last known duel in Missouri resulting in bloodshed actually happened a few years later, from 1861 to 1864, at a time when shooting other people was sort of legal as long as you were part of a big enough team. Did the custom of semi-acceptable individual dueling contribute to the outbreak of the group format? It didn’t help, according to the author of a terrific history book about prewar Congressional dueling called The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War (affiliate link, so if you buy it Amazon will fling a few pennies at me). I have found legislative brawls amusing from time to time, though I probably shouldn’t. But if you think things are bad now, consider antebellum Congress, where “legislative sessions were often punctuated by mortal threats, canings, flipped desks, and all-out slugfests,” according to the blurb. Pistols and knives were waved at opponents during heated debates.

This would all make C-SPAN much more interesting, of course, but even so this probably isn’t something we should encourage. It can lead to unpleasantness.